Beyond the Cube: Ancient Puzzles and Mythic Riddles That Inspired the World

Explore the historical ancestors of the Rubik's Cube, from Archimedes' Ostomachion and the Gordian K...

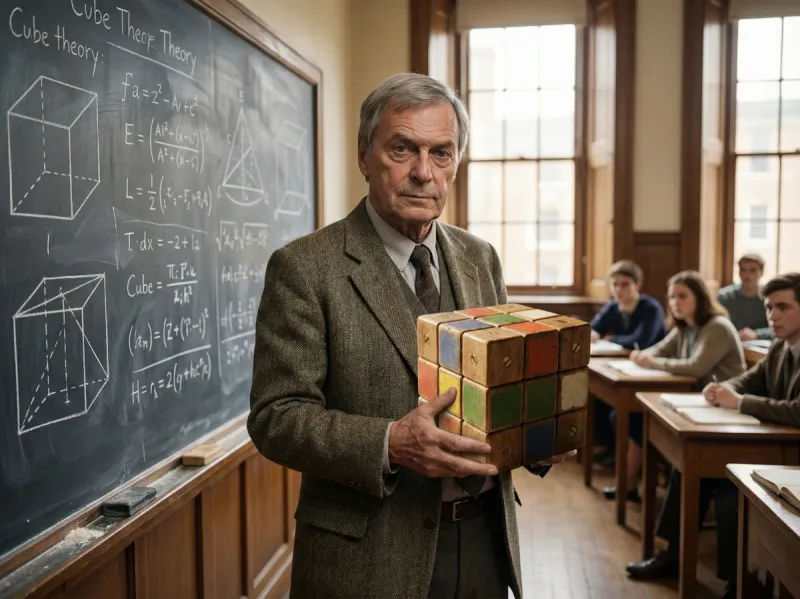

In the spring of 1974, in a small apartment in Budapest, Hungary, a young architecture professor named Ernő Rubik was obsessed with a geometrical problem. He wanted to create a structure that allowed individual parts to move independently without the entire mechanism falling apart. He wasn't trying to create the world's best-selling toy; he was trying to teach his students about 3D space.

The very first iteration of what we now know as the Rubik's Cube was handcrafted by Ernő himself. Using wood, rubber bands, and paperclips, he fashioned a 3x3 block. When he finally realized he had created something unique, he applied for a Hungarian patent for his 'Magic Cube' (Bűvös Kocka) in 1975.

Beyond the basic history, there are several fascinating details about the cube's early days that even seasoned speedcubers might find surprising:

One of the most mind-blowing facts about the cube is the sheer number of possible permutations. There are 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 (43 quintillion) ways to scramble a 3x3 cube. If you were to try every single combination at a rate of one per second, it would take you 1.4 trillion years to see them all!

By the early 1980s, 'Cubing' became a global craze. While many thought it was a passing fad, the invention of the internet and the rise of the World Cube Association (WCA) turned it into a competitive sport known as speedcubing. Today, we have 'God’s Number'—the mathematical proof that any cube can be solved in 20 moves or fewer—a concept that would have seemed like science fiction to Ernő in his Budapest apartment fifty years ago.

The Rubik's Cube remains a testament to human curiosity and the beauty of structural design. What started as a simple wooden tool for an architecture class has evolved into a symbol of intelligence, perseverance, and global community. Next time you pick up your cube, remember that you aren't just holding a toy; you're holding a piece of architectural history that even its creator struggled to master.